|

Martyrs of New GuineaSunday 2nd September, 2001

|

|

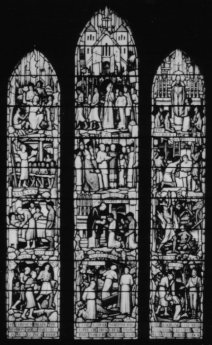

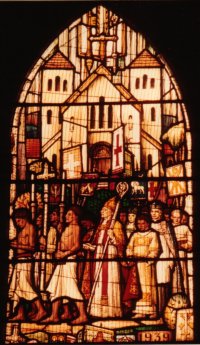

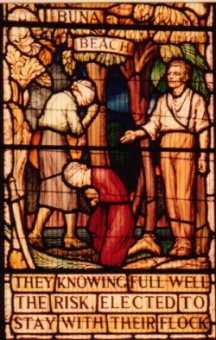

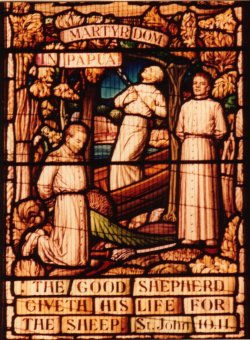

There are groups of missionaries nursing, teaching, or celebrating the eucharist; and in the centre light in the top two panels, the procession at the consecration of Dogura cathedral and the reading of the license of consecration in 1939, in which Sir Philip Strong, Bishop Wand (then of Brisbane), Bishop Newton (Strong's predecessor in New Guinea), and other individuals, can be clearly recognised. Sir Philip Strong, in a sermon delivered close to the end of his life, invited viewers to look at the lower panels as though they represented particular martyrs or groups of martyrs, but his wording makes it clear that he did not think that the artist was presenting them as individual likenesses of the martyrs.[1] In point of fact, Waller had access to photographs of the consecration of Dogura cathedral which Fr Maynard brought back with him, and which remain in a photograph album in the parish archives. But we have no evidence that he had access to any likenesses of the martyrs themselves. For them, the representations are generalised ones.

These are far from being the only visual representations of the New Guinea martyrs. Waller created another window in 1972 showing Vivian Redlich, an English-born bush brother from Queensland, and two nurses, as part of a much larger cycle of windows in St Mark's, Camberwell. When it comes to representing the martyrs in terms of historical likenesses, the significant group of windows in an Australian church are those by William Bustard in St Augustine's, Hamilton, in Brisbane. They are part of a large west window, completed as a war memorial in 1948, showing Christ surrounded by the saints in glory. The nurses Mavis Parkinson and May Hayman and the priests Vivian Redlich and John Barge are shown, with their names to distinguish them individually in their haloes.[2] Unlike Waller, it was easy for Bustard in Brisbane to have access to photographs of these particular individuals, given their Queensland links. Most recently, an image of Lucien Tapiedi was created for Westminster Abbey as part of a group of Anglican holy men and women from all around the world.

The subject matter of the New Guinea windows in this church, and the others to which I have referred, is certainly important in itself. It is vital for us to be reminded that we are surrounded by a glorious company of witnesses. Visual representations of these and other holy ones can always do just this for us. But they also share three themes or attitudes in common with a number of other windows and art works found in Anglican churches in Australia, and rarely, if ever, in this form beyond them.

Firstly, these windows show people who were living contemporaries of their first viewers and of the artists who created them. I have already referred to the presence of bishops such as Strong, Wand and Newton present at Dogura cathedral's consecration, and even Maynard. If we look across into the south transept, another such example can be seen – the figure of Bishop Gore, a founder of the Community of the Resurrection, and Christian socialist, whom Maynard had met not long before his death, during the great Depression. Gore's theological publications influenced Maynard and many others; he is represented in the window, seated in his purple cassock, surrounded by some of the children who already lived in poverty on the streets of the great industrial centres of England. In St Mark's, Camberwell, there is a World War II memorial showing, not some representative unknown serviceman, but a specific individual – an airforceman, Andrew Seton Campbell, who was killed on an air raid over Labrador in 1943. Or at an even more personal level, a window in St John's, Bairnsdale, shows a young man, David Lethbridge (1944-67), surrounded by symbols of sport and education. A window such as this last one can certainly be interpreted as a highly personal symbol of an individual family's affection, known and accepted in a local community; not the result of a more broadly based recognition of qualities by a larger and more comprehensive group. But even when we acknowledge that kind of limitation in this last kind of case (and there are a number of others like it), all representations of contemporary or near contemporary figures – well-known and obviously universal in their reference, or far more individual – may be seen as making the same very positive proclamation: it is now, not in some time past, that Christian values are to be lived out and encountered in people's lives. Now is the hour of salvation. The present can be the holy. And it is the co-operation of contemporary people which will ensure the sanctification of the present.

The second insight is embodied in windows that are not discrete or self-contained units, but are part of a larger, deliberately conceived, cycle. I referred earlier to the Napier Waller window of some of the New Guinea martyrs in St Mark's, Camberwell. You can also find Melbourne's first Anglican bishop, Charles Perry. Most of the windows in that church are part of a cycle devised by one man, Canon PW Robinson, even though the windows were executed by several glass artists over a period of time. The key is the great hymn of praise from the 4th century, the Te Deum. The praise of God and the glory of God are seen in key events in the life of Jesus; the glory of Christ is revealed in the Transfiguration (a major set of windows), and likewise in an extraordinary range of men and women. There are the predictable New Testament holy persons, and Anglo-Celtic saints, great medieval figures such as saint Boniface; reformation theologians such as Nicholas Ridley and Thomas Cranmer, and then more recent significant Anglicans such as John Keble, and two reformers in different areas of life, the Earl of Shaftesbury and Florence Nightingale. Recent Anglican martyrs from other parts of the world are there, in the form of Bishop Hannington and the martyrs of the 1880s in Uganda. The cycle also includes figures such as David Livingstone and Edith Cavell, who have never been formally regarded by any church as saints, but I think that we can only rejoice in the breadth, the true catholicity, of such an all-encompassing vision of holy and sacrificial living, a breadth of vision that is characteristic of Anglicanism at its best. Seen in the context of this broad range, the experience of Anglicans in Australia and the Pacific, such as Perry or the New Guinea martyrs, though recent in itself, is not some isolated, odd phenomenon in an alien setting. Anglicanism is presented as part of a great stream, flowing through time and across the known world in many different channels of human experience. To use a word rather fashionable at present, they show us to be connected – but in a way that is completely Catholic.

There are other cycles of windows in other Anglican churches which encapsulate the same insight, though with not quite the same richness, ranging from the Norman St Clair Carter windows in St Andrew's cathedral, to the windows on the south side of St John's, Malvern.

There is a third and last proclamation: made both by the various windows of the New Guinea martyrs and by yet another range of subject matter in windows and other art works in our churches. If you look over the west door of Wangaratta cathedral, you will see a group of windows from the early 1960s, late product of the Melbourne firm of Brooks Robinson not long before they closed. In the top panels, a vested priest, accompanied by a server, stands at an altar offering the eucharist. Accompanying this subject is the liturgical text 'Here we offer and present unto Thee O Lord our souls and bodies'. Below them, the space shows a series of landscapes, commencing with pioneer settlement, but going on to show a twentieth century town and housing, a modern factory and farm equipment. Here, in Australia, in this place, not somewhere else, the offering continues: the windows present the Australian landscape and our modern developed urban centres as the place where Christ offers Himself. In a more general way, windows and other representations of the New Guinea martyrs make the same point – Christ's glory is seen by 20th century people in the Pacific region; it isn't a revelation confined to the Middle East, or the old world of Europe and earlier saints. It is in our region, in time that is a living memory for many of us. And there are other many other windows in our churches that affirm Christ's presence as very much here, as well as now. Not all are necessarily aesthetic masterpieces. I think of a quite sentimental treatment of subject matter (as well as the colour of the glass) in a window in St Andrew's, Brighton; a memorial to a young woman who was a lover of Wilson's Promontory. Here, Mary Magdalene is seen visiting the tomb in an Australian landscape dotted with rosellas and other local fauna; or there is the 1979 window with an almost kitsch treatment of St Francis in the manner of a 1920s Brooks Robinson window now in St Silas, Albert Park, showing St Francis with a rosella on his shoulder and a kangaroo looking up in wonder from in front of him. But there are other sharp and masterly examples. In the cycle of windows by Cedar Prest in St Peter's cathedral in Adelaide, there is a group called 'The Message of Hope'. In it are some of the New Testament incidents in which Jesus acts in an inclusive way across religious and cultural boundaries. There is the Samaritan woman at the well; and the feeding of the 5000. But this feeding happens at night, and in a setting that includes the bandstand in the park near St Peter's cathedral. It is about finding Jesus here. The compassion of the Good Samaritan, and of Simpson and his donkey, contrast with Asian refugees detained behind barbed wire, famine victims, and aboriginal people dying in custody. The gadarene swine, rushing down a diagonal behind aboriginal figures, is a thinly-veiled and pointed reference to police abuses. Cedar Prest's windows are about Christ, not 2000 years ago in Palestine, but today in Australia, being accepted or rejected.

The contents of these windows that we see in both transepts, and of others to which I have referred, are not just a matter of attractive ornament, or of an encouragement to high quality aesthetics. If we allow them, they affirm central Catholic insights about the life of Christ in His holy ones. It is part of a great procession in which we connect with a recalled past. But it is not past; it is here and now.

Notes and detailed illustrations

|

|

Some | |

|

Views is a

publication of

St Peter's Eastern Hill, Melbourne Australia.

|

Authorized by the Vicar

(vicar@stpeters.org.au) |