Consider the Lilies

Ordinary Sunday 8: 2nd March, 2014

Rev'd Dr Hugh Kempster, Vicar of St Peter's, Eastern Hill

Isa. 49:13-15; Ps. 62:1-8; 1 Cor. 4:1-5; Matt. 6:24-34

Depression is a huge issue in our society. The label "depression epidemic" is somewhat contentious, but certainly the clinical diagnosis and pharmacological treatment of depression are more prevalent than ever. The World Health Organisation identifies depression currently as "the leading cause of disease burden for women in both high-income and low- and middle-income countries" above heart disease or diabetes. They predict that unipolar depressive disorders will top the global burden of disease table by 2030.[1] Australian Bureau of Statistics figures point to younger people as most at risk, with a staggering 26% of 16-24 year olds experiencing symptoms of a diagnosed life-time mental disorder in the 12 months prior to the survey.[2] My guess is that depression or anxiety is something that touches each one of us; whether we suffer from it personally, or know someone who does.

Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, or about your body, what you will wear ... consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you — you of little faith?

It would be naïve, even cruel of me to pretend that these words of Jesus are a panacea, a quick fix, or even a judgement on those who struggle with the "black dog" of depression.[3] Give up the medication, trust more in God; that is not what this passage is about at all. Today's gospel reading is the centre-piece of Matthew's majesterial account of Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. Like Moses bringing down the Ten Commandments from Mount Sinai, the Matthean Jesus delivers the eight beatitudes and proclaims the ethics of the new lawgiver.[4] The exhortation not to worry is set alongside Jesus' teaching on prayer, it is part of a Christological reshaping of traditional understandings of piety. It is a passage about prayer, but more than that, it is a cutting critique of a money-hungry materialistic culture. It is about discerning the root cause of our anxiety, at a societal level; identifying the poison and delivering the antidote.

No one can serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth. Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life ... look at the birds ... consider the lilies.

The increase of depression in our society appears to correlate positively, not negatively, with our increase in wealth. It would seem that more wealth does not bring more happiness, in fact quite the contrary, increased prosperity enslaves us and cuts us off from God and from our neighbour. It tricks us into thinking that our wellbeing is threatened by vulnerable people, that our security is at risk from those fleeing persecution and the horrors of war. How is history (let alone God) going to judge us, as we wealthy Australians imprison people for the crime of asking for help and refuge? Mammon is a cruel master indeed. Lord Wealth keeps us so busy, so stressed, so anxious that we have no time to look at the birds or consider the lilies or have compassion for the stranger.

On Friday last week I was rushing back to St Peter's after delivering a lecture at Trinity College Theological School. I was late for an appointment, but I ended up stopping to talk to a man who was sitting on a bench in the church grounds. He was a well spoken and well dressed man, clearly taking a break from work. "I'm not religious," he said, "but I've started coming here each day. It makes such a difference to my stress levels, just sitting here in the sun, or in church. It gives me time to think; time to be."

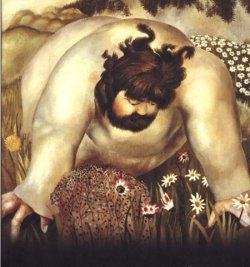

Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), one of the great English artists of the twentieth century, painted a provocative theological reflection on today's gospel reading entitled "Christ in the Wilderness: Consider the Lilies" (1939). It depicts a fat, tousled, even playful Jesus considering not lilies but daisies. The Christ is intentionally child-like, as the artist himself explains: "I think I got this notion from first having made a small study of [my daughter] Shirin when she was a baby out on the grass ... the leaning over the flowers gives me a sense of the Creator brooding over his creation, and the analogy between what a baby might do and what God might do is so near in its feeling."[5]

Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), one of the great English artists of the twentieth century, painted a provocative theological reflection on today's gospel reading entitled "Christ in the Wilderness: Consider the Lilies" (1939). It depicts a fat, tousled, even playful Jesus considering not lilies but daisies. The Christ is intentionally child-like, as the artist himself explains: "I think I got this notion from first having made a small study of [my daughter] Shirin when she was a baby out on the grass ... the leaning over the flowers gives me a sense of the Creator brooding over his creation, and the analogy between what a baby might do and what God might do is so near in its feeling."[5]

The Christ figure, large, powerful, God-like, stops to gaze at the smallest and most fragile thing; perhaps in wonder, perhaps in praise. I wonder, is this how God sees us, is this how God wants us to see others? As we pause and ponder with the Christ, our attention is drawn, like him, to three daisies with red tips to their leaves. Is this blood? In the stillness we are drawn into solidarity with those who suffer; into the crucifixion. In this place of pain and death we might then notice a single golden dandilion to the far left of the painting; new life, hope, resurrection.

Stephen Cottrell has published a beautiful theological reflection on this painting, and others in the "Christ in the Wilderness" series, which is well worth reading. He closes this chapter with the well known words of Nadine Stair, purportedly written in her 80s:[6]

If I had my life to live over, I'd dare to make more mistakes next time. I'd relax; I would limber up. I would be sillier than I have been this trip. I would take fewer things seriously. I would take more chances. I would climb more mountains, swim more rivers, and watch more sunsets. I would eat more ice cream and less beans. I would perhaps have more actual troubles, but I'd have fewer imaginary ones.

You see, I'm one of those people who lived sensibly and sanely, hour after hour, day after day. Oh, I've had my moments, and if I had to do it over again, I'd have more of them. In fact, I'd try to have nothing else, just moments, one after another, instead of living so many years ahead of each day. I've been one of those persons who never goes anywhere without a thermometer, a hot water bottle, a raincoat and a parachute. If I had to do it again, I would travel lighter than I have.

If I had my life to live over, I would start barefoot earlier in the spring and stay that way later in the fall. I would go to more dances. I would ride more merry-go-rounds. I would pick more daisies.

Notes:

- C Mathers, T Boerma, & D M Fat (2008) The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization (pp 46, 51).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2007). National survey of mental health and wellbeing: Summary of results (Cat. no. 4326.0), Canberra (P. 9).

- On the metaphor "Black Dog" to describe depression, see the Black Dog Institue website

- R Brown (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. New York, Doubleday (pp. 178-9).

- S Cottrell (2012). Christ in the Wilderness: Reflecting on the Paintings by Stanley Spencer. London: SPCK (p. 50).

- Cottrell, Ibid.. (p. 54).

|

Views is a

publication of

St Peter's Eastern Hill, Melbourne Australia.

|