|

In 1890 he edited a collection of essays by different writers, Lux Mundi: A Series of Studies in the Religion of the Incarnation. This collection attempted to renew the faith by bringing the Christian creed into a better relationship with modern knowledge and critical thinking in science and history, and relating it more directly to emerging problems in politics and ethics. The book emphasized the doctrine of the Incarnation; this was a departure from traditional thinking in which the doctrine of the Atonement was central to Christianity. The young writers of Lux Mundi saw that to repel the attacks of modernism, it was necessary to restore the doctrine of the Incarnation, with its social as well as its theological implications, to its true position in relation to the whole Faith. As Gore wrote many years later, 'The truth about our Lord's humanity came to us with a fresh thrill of delight.'

The publication of these essays caused some pain and anguish among the older, more traditional members of the Oxford Movement. This pained Gore also, and in a new preface to the tenth edition of Lux Mundi he stressed that the essayists were writing for Christians, particularly for Christians who were perplexed by new knowledge and new problems. In such perplexities a readjustment of faith and knowledge, such as had taken place in the past, was necessary to show that science is not irreligious, nor is religion hostile to knowledge.

In 1892, Gore founded a clerical fraternity known as the Community of the Resurrection at Pusey House. In 1898 the House of the Resurrection at Mirfield, near Huddersfield, became the centre of this community, and in 1903 a college for training candidates for the priesthood was established there.

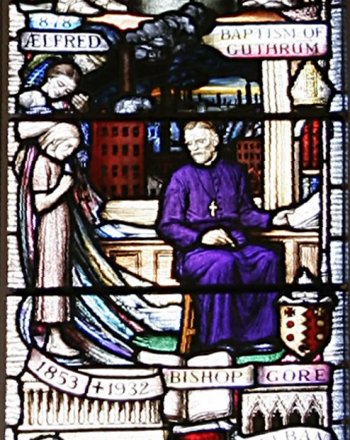

Dr Gore was consecrated Bishop of Worcester in 1902, and, when the new diocese of Birmingham was split from the See of Worcester in 1905, he was installed as its first bishop. In 1911 he became Bishop of Oxford; remaining there until 1919 when he went to live in London, where he continued to wield considerable influence through his writing and preaching. Bishop Gore died in January 1932.

Zeal for social righteousness was one of the central passions of Gore's life. He helped found the Christian Socialists Union at Pusey House in 1889. This was a group of High Churchmen whose purpose was the practical application of the Incarnational doctrine which had been stated in Lux Mundi. From the doctrine that Christ was Very Man, it followed that His Body the Church must express humanity at its fullest and best as a universal brotherhood, and must stand firmly for social as well as personal righteousness. The objectives of the CSU embodied the general principle that Gore frequently stressed—that it was impossible to be a true Christian without applying the teachings of Christianity to the practical affairs of life. The importance of study was also stressed, and Gore insisted that careful inquiry must precede action then, when the facts were known, the Christian solution must be boldly applied. In its practical work, the Union led crusades against slums, and against the use of leaded glaze in pottery which was so damaging to the health of workers in the Midland potteries.

This aspect of Gore's work, with its emphasis on the 'Social Gospel', lies behind the portrayal of Gore in the window. Not that Gore himself ever accepted the Socialist political creed; for the greater part of his life he was generally a Liberal in politics. Although in his later years he was strongly drawn to the Labour Movement, he could not shut his eyes to its shortcomings. For him, the demand for rights must always be accompanied by the readiness to perform the corresponding duties.

Bishop Gore's theology and social conscience had a great influence on Canon Maynard. Themes that were important to Gore continually appear in Maynard's sermons, and Bishop Gore's determination to apply Catholic principles to social problems and contemporary issues influenced Maynard throughout his life.

Previous |

Index |

Next

|