|

|

The Eye of God |

Nicholas of Cusa and the IPCC ReportDelivered by Dr Graeme Garrett, formerly of St Mark's National Theological Centre and sometime editor of St Mark's Review, at the Institute for Spiritual Studies on Thursday the 14th of November, 2013.

The idea — or symbol — of 'the eye of God' also has a powerful and long-standing place in Christian tradition. Biblical references to God's watchfulness abound. For example (Ps 33.13f): 'The Lord looks down from heaven; he sees all humankind. From where he sits enthroned he watches all the inhabitants of the earth ...'. This sense of the unfailing watchfulness of God has ambivalent implications. On the one hand, it can mediate a feeling of security, a sense that our lives are held firmly in the Providence of a loving and attentive God. 'The eyes of the Lord are on the righteous, and his ears open to their cry.' (Ps 34.15) Very reassuring. But on the other, it has a threatening, disquieting aspect. If nothing is hidden from the eye of God, then our treacheries and infidelities, our lies and our violence, are open to God's scrutiny. 'And before him no creature is hidden, but all are naked and laid bare to the eyes of the one to whom we must render an account.' (Heb. 4.13) Not so comforting.

One man who took up the idea of the eye of God and meditated deeply on both its theological and practical significance was the great German mystic, Nicholas of Cusa.

That said, I want to turn to Nicholas' mystical theology, by which I mean his understanding of our human experience of God; not just believing in God, still less believing things about God, but a living engagement with God. 'What is it, Lord, that Thou conveyest to the [human] spirit ...?' asks Nicholas. 'Is it not Thy good Spirit, who in His Being is consummately the power of all powers and the perfection of the perfect, since it is He that worketh all things.'[1] These words appear in this little book, The Vision of God. It was first published in December of 1453. Nicholas occasionally spent time with the monks of the Benedictine Abbey at Tegernsee in southern Bavaria. After one such visit in June 1452, the monks were so taken with his conversation about prayer and the mystical life that they begged him to return and give them further instruction in the contemplative life. From that time on Nicholas seems to have acted as a sort of spiritual director to the community. This book, which has become the most famous and enduring of his writings, was the guide he prepared for the Tegernsee monks.

His book is an extended meditation on the meaning of this ocular image. For one brought up in the Protestant tradition with its heavy emphasis on the voice and the word, this shift to a focus on vision and the eye of God is challenging and refreshing. But before we get to the details a preliminary point is important. Nicholas reflects at length on the figure of the eye. But it is not random theological speculation. He is not engaged in what used to be called 'natural theology'; using a particular image, the eye in this case, and extrapolating from it to supposed divine characteristics that are in some way like it. His interpretation of the vision of God is saturated in the Christian narrative, centering in Jesus Christ. He is writing to monks whose daily routine is steeped in the liturgy, the scriptures and the tradition. The whole of the latter part of the book moves into an exposition of God as Trinity and Christ and the divine\human mediator between heaven and earth. So this is a Christian view of the eye of God, through and through. The monks asked Nicholas to teach them to pray, to deepen their experience of God. He responds by offering them a simple and easily implemented practice. It has three parts to it. First he provides them with a physical object, a painting; something for them to focus their gaze upon. He wants them to use their eyes. But he wants their gaze to be an informed gaze. They are not just to gawk at the painting, but to look at it with particular intention. So he provides them also with a manual of instructions. This book. The book is education for their eyes. A handbook on how to see. Second he asks them to act on his instructions. It is not enough to read the book and look at the painting, It has to be enacted bodily, put into practice in the real world. And third — and this I find a fascinating thing — Nicholas says to his monks, you need to talk about the experience afterwards with your companions. To learn to see the God who in seeing us calls us to be and to see, we need the conversation and encouragement of fellow-believers. This kind of seeing is an ecclesial seeing. So let us turn to the details of this spiritual practice. 1. The painting and the instructions:

For Nicholas to see this, to see these eyes that gaze at you continually and irrespective of where you are, is to have a real intimation of God; an intimation of that primal, providential eye that precedes the world and continually embraces the creatures of the world in its perfect vision. Nicholas is strongly influenced by Augustine's understanding of creation. All beings, including human beings, are drawn from the void of nothingness by the creative intention and foreknowledge of God, according to Augustine's interpretation of the Genesis narrative. Nicholas transposes this into his visionary framework. The eye of God beholds the world; but not as one who looks on to an independent object, as with our gaze. God's gaze produces the very thing it beholds. He writes: 'For Thee [God] to see is to cause; Thou seest all things who causest all things.'[4] And again: 'Thy sight ... because it is the cause of all things visible, ... embraceth and seeth all things in the cause and reason of all, that is, in itself.'[5] The world is God's visible vision. When we look at the world we are looking at God's looking at us. This has deep personal implications. 'I exist in that measure in which Thou art with me, and, since Thy look is Thy being, I am because Thou dost look at me, and if Thou didst turn Thy glance from me I should cease to be.'[6] In short, I am seen, therefore I am. My first and most fundamental apprehension of the eye of God is this, my being. Whatever else the eye of God may imply for me, of comfort or threat, the first consequence of that gaze is my life itself. This understanding of the creative vision of God underlies the whole of this handbook on the spiritual life according to Nicholas. But I am getting ahead of myself. An exposition of the mystical theology of the eye of God can only happen if we bodily involve ourselves in the kind of seeing that Nicholas intends to teach his monks. This is an experimental and experiential theology that requires the participation of the monks. 2. The ExperimentThe first step is simple. 'This picture, brethren, ye shall set up in some place, let us say, on a north wall, and shall stand around it, a little way off, and look upon it.'[7] The placement of the image is significant for where it isn't. It isn't in the chapel. Nicholas wants them to mount it on a wall that is part of the ordinary life of the community, perhaps in the refectory or the reception hall. His spiritual exercise is not designed to be part of the formal liturgy of daily worship. The theology of the eye of God is intended to concern the monks in the place of ordinary everydayness. The picture is not to draw them into some sacred space set apart from the world in which they live. This is an important point which I will come back to a bit later. Having set the painting on the wall, the monks are to stand around it in a sort of semi-circle, one to the east side of the image, another to the south, and another to the west. From their various positions, they look at the painting. What do they see? According to Nicholas' 'each of you shall find that, from whatever quarter he regardeth it, it looketh upon him as if it looked at none other.'[8] Each sees the eyes of Christ regarding him in his spot. And yet all experience the same thing at the same time. If now the guy on the east moves across to the west of the image and guy on the west across to the east, both will discover the eyes rest upon them in the new location exactly as they had previously. Do this exchange, says Nicholas, and 'ye will marvel how it can be that the face should look on all and each at the same time.'[9] Immersed in this practical experience, Nicholas then invites his monks to imagine the phenomenon extrapolated to infinity. The eyes of the icon has these astonishing properties. But the eye of God has them to perfection and universally. 'Thou, Lord, seest all things [not merely a community of monks] and each thing at one and the same time, and movest with all that move, and standeth with them that stand.'[10] And they divine eye attends to all with the same untiring tenderness, '... it taketh the same most diligent care of the least of creatures as of the greatest, and of the whole universe.'[11] And yet such is its particularity that every creature which so 'findeth himself observed' senses this gaze 'as though it cared only for him, and for no other'.[12] At this point Nicholas calls explicitly on the Christian revelation to spell out his meaning. In an extended and quite beautiful section of the book he adopts Augustine's interpretation of God as Trinity in terms of a unity of love between the Lover (Father), the Beloved (Son) and the bond of Love between the two (Holy Spirit).[13] The essence of God is the essence of love. Thus the eye of God (the Trinity) looks upon the world as the eye of love. Then, referring directly to the experiment with the painting, Nicholas writes: I prove by experience that Thou lovest me because Thine eyes are so attentively upon me, Thy poor little servant. Lord, Thy glance is love. And just as Thy gaze beholdeth me so attentively that it never turneth aside from me, even so is it with Thy love. And since 'tis deathless, it abideth ever with me, and Thy love, Lord, is naught else but Thy very Self, who lovest me. Hence Thou art ever with me, Lord; Thou desertest me not, Lord; on all sides Thou guardest me, for that Thou takest most diligent care of me.[14] From this personal sense of the visual care of God, Nicholas extrapolates to universal nature of the loving providential attentiveness of God to the universe at large and all that is in it. It is a very wide vision indeed. That this is a very positive, even rosey, estimation of the meaning of providence is evident. But Nicholas is not unaware of the threatening dimensions of the eye of God. He knows full well the human heart is fickle and fallible. We turn away from God. We oppose the intentions of God in the world. Violence, injustice, lies and hatred are all around. Such an opposition to God has serious consequences. It drags us away from the source of life and sucks us into the consuming vortex of nothingness. 'If Thou regardest me not, 'tis because I regard not Thee, but reject and despise Thee,'[15] he says. And yet, for Nicholas, the fundamental truth of the gospel remains always the grace and mercy of God. And this is the innermost truth of a mystical theology of the eye of God. For with Thee 'tis one to behold and to pity. Accordingly,Thy mercy followeth every man so long as he liveth, whithersoever he goeth, even as Thy glance never quitteth any. So long as a man liveth, Thou ceaseth not to follow him, and with sweet and inward warning to stir him up to depart from error and to turn unto Thee that he may live in bliss.[16] Karl Barth would wholeheartedly concur with Nicholas on this point. Humans may become godless. But God will never become human-less. In Christ God has united himself irrevocable with the world and intends to bring the world at last into God's kingdom of love. 3. The ConversationNicholas has one final instruction to his monks. It has to do with community. If we genuinely wish to behold the eye of God that beholds us, that is to experience God's providential love, we need another to bear witness to our experience. Try this, he says. One of you, while keeping your eye on the icon, walk from west to east around it. You will find that the gaze of the eyes moves continuously with your walking. And then if you turn and walk the other way, from east to west, in like manner the eyes follow all the while. That is remarkable enough. But now complicate the experiment. While you walk from west to east all the while noting the eyes upon you, have your fellow monk walk at the same time from east to west. When you meet in the centre before the picture ask the other if the gaze of the icon turned continuously with him as it did with you. The one who asks, says Nicholas, will hear that it doth move in a contrary direction, even as with himself, and he will believe him. But, had he not believed him, he could not have conceived this to be possible. So by his brother's showing he will come to know that the picture's face keepeth in sight all as they go on their way, though it be in a contrary direction. This is a remarkable statement of ocular mystical theology. For Nicholas genuine faith (he calls it here 'belief') in the providential eye of God is made possible only in community. I cannot move in two directions at once and hence confirm for myself the universal moving vision of God. For that I need your confirmation, your complimentary witness. The will to share the astonishment and to believe the word of the brother or sister that is expressed in the question 'You too?' lies at the foundation of spiritual practice of Nicholas of Cusa. The vision of God requires an ecclesial seeing. We do it together, not as isolated individuals. Confidence in the providential love of God is a con-fidence, a faith shared, a faith that is talked about with the other, the fellow traveller, the fellow believer. To sum up. Nicholas' spiritual exercise has three dimensions to it. (i) an object of focus for the eye (the picture) with accompanying guidelines on how to relate to it (the book); (ii) a bodily practice in which we and others physically interact with the focal object in a directed way; and (iii) a mutual and trusting conversation with fellow pilgrims equally committed to a deepening of our human experience of God. 4 The IPCC Report2013 Melbourne is very different from 1453 Cusa. If by some miracle Nicholas were to be present here and now, and if we, like the monks of Tegernsee were to ask him, 'Teach us to pray', or 'show us the vision of God', how might he respond?

I think this picture would appeal to a modern day Nicholas charged with the daunting task of helping us spiritually. But he wouldn't send us this picture to hang on our wall. I think he would ask us to do what Friedrich's monk has done. Leave the cloister, go out into world, not the human world of the city and the society, but the wide world of nature, of the sea, the air, the sky, the earth. For we in the urbanised, consumer society of the west have become largely alienated from the splendours of the world of

And what text might he send us to read in order that we might look at the world with appropriately receptive eyes? Nicholas was a scientist; he would have known what was happening in and to our environment. And he would have been aware of its spiritual significance. He might well ask us to read the latest IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Report, which came out on 27th September. The IPCC is widely recognised as the leading international body for the assessment and articulation of climate change knowledge. The full report runs into hundreds of pages of closely argued science, which most of us are probably ill-equipped to follow in detail. But the IPCC has condensed its findings into a few pages of clear and comprehensible statements which set out the current state of expert knowledge in the area of climate change in a way that all of us can grasp.[17] The main lines of its argument are summed up in three short statements. a) 'Warming of the climate system is unequivocal'. Although it is becoming less frequent, perhaps, there is still a tendency in some areas of public debate to put a question mark against claims that significant macro-changes in global climate is under way. This report makes the credibility of such claims very hard to sustain. On the basis of detailed research over 25 years the report concluded: Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and the concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased.[18] Each of these changes has serious implications for life on Earth, our own as well as other species and the Report describes these in scary detail. b) 'Human influence on the climate system is clear.' Although both sides of politics in the recent election campaign agreed that the weight of scientific option supports the reality of anthropogenic climate change, there are still powerful counter arguments swirling in the Australian public domain. Voices disputing human influence in global climate variation are often cited as if they carried an equal authority within the scientific community. The report pretty comprehensively reveals such claims to be groundless. There is no genuine disagreement in the contemporary mainstream scientific community over human induced influence on climate. The report states: Human influence has been detected in warming of the atmosphere and the ocean, in changes in the global water cycle, in reductions in snow and ice, in global mean sea level rise, and in changes in some climate extremes. ? It is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.[19] c) 'Limiting climate change will require substantial and sustained reductions of greenhouse gas emissions.' In Australia we face some tough decisions. With large reserves of coal and gas, and with an economy geared massively to oil based energy, we find ourselves, on a per capita basis, at the top end of carbon emitting countries. The clear message of the IPCC is that we need to change our ways quickly and drastically. 'Continued emissions of greenhouse gases will cause further warming and changes in all components of the climate system.'[20] These would include:

Armed with this contemporary icon and an interpretive text to go with it, what spiritual practice might a present day Nicholas commend to us? I think it would be to widen our practice of prayer and contemplation beyond our personal world, beyond our social and ecclesial worlds, to include the natural world; the world which this eye of God beholds and in beholding creates and sustains. I have learned a lot from the spirituality of indigenous people. They have not forgotten, as I have, how to place themselves as living participants in the world of air, and sky, and fire, and water (the eye of God tapestry); to attend in reverence and awe to these fellow beings upon which we depend. My stuttering efforts at reform have been to go to the seaside, like Friedrich's monk and to stand for thirty minutes and give undivided attention to the sight, the sound, the touch, the taste, the feel of the ocean; to try to see it as being seen by the loving eye of God, that Nicholas talks so movingly about; and in that joint seeing, to find myself engaged with God whose creative work this great ocean reality expresses in every movement, colour, sound, and silence. It is a salutary experience, especially since I have started to read the literature on the damage we are doing to the oceans and their inhabitants. You remember that moment in the gospel story where Peter in the courtyard of the high priest's palace denies with curses to a servant girl that he ever knew Jesus now condemned to death. The cock crows. And the text says, 'The Lord turned and looked at Peter' (Lk 22:61). What would have passed between them with that look? For Nicholas of Cusa it would not have been a look of hostility or rejection, but a look of saddened love; saddened for what his actions had done to Christ, but saddened also for what they had done to Peter. To contemplate the wounded sea with an eye that recognises that the sea and myself are held in the loving gaze of God is to feel powerfully the saddening of God's gaze at what my actions are doing to the world that God loves. But it is also to discover anew that mercy which is unfailing. 'For with Thee 'tis one to behold and to pity ... Thy mercy followeth every [one] so long as they liveth, [and] whithersoever they goeth, even as Thy glance never quitteth any.'[21] Finally, our modern day Nicholas would ask us to talk to each other about our various experiences with the universal eye of God. There is a lot of thought and action going on in society and in church about these central challenges of our time. We need to talk with each other; learn from each other; encourage each other; act with each other. The science and the politics are vital of course and we must attend them. But something more is needed to sustain the repentance, change of life and building of new hope that is required of our times. We need to recover something like Nicholas of Cusa's reverence, indeed adoration, of the world as the creation and God's providential loving gaze and to learn with him that when we look upon the world we are looking upon God's looking on us; and exult in that; and respond to that in ways that are fitting not fouling.

Perhaps Gerard Manley Hopkins is the Nicholas of Cusa for our times. Notes

This site is hosted by St Peter's Eastern Hill,

Melbourne, Australia. |

Many of you may be familiar with this spiritual object. It is called 'the eye of God'. Such artefacts are found in many indigenous cultures, especially in Mexico and amongst Native American Indians. This one comes from Montana in the USA. As you can see it is woven from woollen yarns of different colours on a simple frame composed of a cross made from two sticks. The four points sometimes represent the elemental processes of creation: earth, fire, air water. In different cultures such objects hold different meanings. But in general, as the name suggests, this represents the all-seeing eye of Providence; the eye of God which has the power to observe and guide the destiny of people; the eye which, ever watchful, apprehends the mystery of our being.

Many of you may be familiar with this spiritual object. It is called 'the eye of God'. Such artefacts are found in many indigenous cultures, especially in Mexico and amongst Native American Indians. This one comes from Montana in the USA. As you can see it is woven from woollen yarns of different colours on a simple frame composed of a cross made from two sticks. The four points sometimes represent the elemental processes of creation: earth, fire, air water. In different cultures such objects hold different meanings. But in general, as the name suggests, this represents the all-seeing eye of Providence; the eye of God which has the power to observe and guide the destiny of people; the eye which, ever watchful, apprehends the mystery of our being.

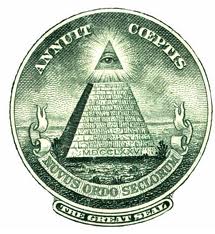

Christian iconography is rich in representation of this theology of God's eye. On the whole, it builds its depiction based on this simple design. Here is the watching eye, an unblinking gaze directed outward towards us. The eye is placed in the centre of a triangle, a classic image of the Trinity. The God who watches us not just any old divinity, but the God who has revealed Godself as our creator and origin, as our companion in Jesus, as our enlivening comforter in the presence of the Holy Spirit. The eye of God radiates light that illumines our darkness and penetrates hidden mysteries.

Christian iconography is rich in representation of this theology of God's eye. On the whole, it builds its depiction based on this simple design. Here is the watching eye, an unblinking gaze directed outward towards us. The eye is placed in the centre of a triangle, a classic image of the Trinity. The God who watches us not just any old divinity, but the God who has revealed Godself as our creator and origin, as our companion in Jesus, as our enlivening comforter in the presence of the Holy Spirit. The eye of God radiates light that illumines our darkness and penetrates hidden mysteries.

Here is a full blooded example of the imagery. The eye of God carved into the façade over the entrance way to Salta Cathedral in Argentina. God watches over our coming in and going out. But not just in the Cathedral.

Here is a full blooded example of the imagery. The eye of God carved into the façade over the entrance way to Salta Cathedral in Argentina. God watches over our coming in and going out. But not just in the Cathedral.

Here is a famous political and economic use of the same image. The eye of God on the great seal of the USA on the reverse side of the greenback. This seems an astonishingly confident interpretation of Providence. God watches over the building of the United States ... this unfinished pyramid with 13 steps representing the 13 original states, awaiting further development. With the words 'Annuit Coeptis' ... 'He approves (or has approved) our undertakings'. 'Novus Ordo Seclorum' ... 'New Order of the Ages'. In short, God's providence undergirds and guides our political and economic ambitions! The writer to the Hebrews might have reservations about such an unqualified claim to the eye of God as an eye of approval.

Here is a famous political and economic use of the same image. The eye of God on the great seal of the USA on the reverse side of the greenback. This seems an astonishingly confident interpretation of Providence. God watches over the building of the United States ... this unfinished pyramid with 13 steps representing the 13 original states, awaiting further development. With the words 'Annuit Coeptis' ... 'He approves (or has approved) our undertakings'. 'Novus Ordo Seclorum' ... 'New Order of the Ages'. In short, God's providence undergirds and guides our political and economic ambitions! The writer to the Hebrews might have reservations about such an unqualified claim to the eye of God as an eye of approval.

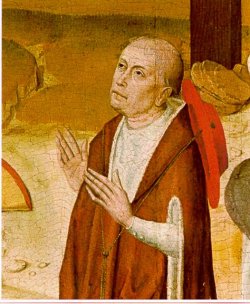

[This painting is thought to be by one Johann van Duyren who worked between 1463 & 1490]. Nicholas was born in the village of Cues on the river Moselle near Trier in south eastern Germany in 1400. He died 64 years later in Rome, a celebrated Cardinal, famous throughout Europe as a churchman, politician, lawyer, theologian, philosopher, scientist, mathematician and mystic. A genuine polymath. Nicholas was also a man of deep prayer and devotion. And it is on this dimension of his life I wish concentrate our thoughts tonight. But it is most important to remember that his spirituality (if I might use that slippery word) was anything but otherworldly or escapist. Nicholas was involved to the hilt in the great affairs of his day. The church was in a state of division and in many places of deep corruption. Nicholas was charged by the Pope to work for reconciliation with the pre-Reformation group called the Hussites, on the one hand, and the Greek Orthodox churches on the other. He was given wide diplomatic powers and responsibility in political matters throughout Germany and in Rome itself. And for all this ecclesiastical and political work, he immersed himself in the cultural and intellectual movements of his time. He was a mathematician, an amateur astronomer, and a first rate philosopher. He even tried his hand at medicine, inventing a way to count the pulse rates of patients. The life of faith and prayer, for Nicholas, was not one that pulled you out of this world into an isolated sphere of the spirit, split off from the challenges of daily life. Quite the reverse. It was a call to unite the human spirit with the life and work of God, the Holy Trinity, in God's continuing formation and transformation of God's creation, of which our human spirit and society is a part.

[This painting is thought to be by one Johann van Duyren who worked between 1463 & 1490]. Nicholas was born in the village of Cues on the river Moselle near Trier in south eastern Germany in 1400. He died 64 years later in Rome, a celebrated Cardinal, famous throughout Europe as a churchman, politician, lawyer, theologian, philosopher, scientist, mathematician and mystic. A genuine polymath. Nicholas was also a man of deep prayer and devotion. And it is on this dimension of his life I wish concentrate our thoughts tonight. But it is most important to remember that his spirituality (if I might use that slippery word) was anything but otherworldly or escapist. Nicholas was involved to the hilt in the great affairs of his day. The church was in a state of division and in many places of deep corruption. Nicholas was charged by the Pope to work for reconciliation with the pre-Reformation group called the Hussites, on the one hand, and the Greek Orthodox churches on the other. He was given wide diplomatic powers and responsibility in political matters throughout Germany and in Rome itself. And for all this ecclesiastical and political work, he immersed himself in the cultural and intellectual movements of his time. He was a mathematician, an amateur astronomer, and a first rate philosopher. He even tried his hand at medicine, inventing a way to count the pulse rates of patients. The life of faith and prayer, for Nicholas, was not one that pulled you out of this world into an isolated sphere of the spirit, split off from the challenges of daily life. Quite the reverse. It was a call to unite the human spirit with the life and work of God, the Holy Trinity, in God's continuing formation and transformation of God's creation, of which our human spirit and society is a part.

Notice the title — The Vision of God. Sight is the central theme of the work; the eye its most formative figure. The title is deliberately ambivalent. The vision of God is both God's prior providential watchfulness across all of God's creation including ourselves, and our derivative finite and fallible vision of God in response. God's eye, with its radiating glory, enlightens and enlivens our eyes, both our physical eyes and the eye of our heart, in response.

Notice the title — The Vision of God. Sight is the central theme of the work; the eye its most formative figure. The title is deliberately ambivalent. The vision of God is both God's prior providential watchfulness across all of God's creation including ourselves, and our derivative finite and fallible vision of God in response. God's eye, with its radiating glory, enlightens and enlivens our eyes, both our physical eyes and the eye of our heart, in response.

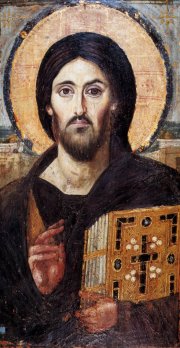

'If I strive in human fashion to transport you to things divine,' says Nicholas to his monks, 'I must needs use a comparison of some kind.'[2] Along with almost all the great mystical writers, Nicholas is acutely aware of the transcendent mystery of God. God exists in a cloud of unknowing that utterly escapes our rational capacities. We need particular objects or images than can help raise our eyes to the hiddenness of God. In general terms we call these things sacraments; outward and visible signs of an inward and transcendent grace. Nicholas sends his monks a picture. Unfortunately for us the actual image has been lost.

But he gives a description of it that allows us to picture it. 'I have found no image better suited for our purpose than that of an image which is omnivoyant — its face, by the painter's cunning art, being made to appear as though

'If I strive in human fashion to transport you to things divine,' says Nicholas to his monks, 'I must needs use a comparison of some kind.'[2] Along with almost all the great mystical writers, Nicholas is acutely aware of the transcendent mystery of God. God exists in a cloud of unknowing that utterly escapes our rational capacities. We need particular objects or images than can help raise our eyes to the hiddenness of God. In general terms we call these things sacraments; outward and visible signs of an inward and transcendent grace. Nicholas sends his monks a picture. Unfortunately for us the actual image has been lost.

But he gives a description of it that allows us to picture it. 'I have found no image better suited for our purpose than that of an image which is omnivoyant — its face, by the painter's cunning art, being made to appear as though

looking on all around it.'[3] We are familiar with the painted face whose eyes seem to follow us and rest upon us wherever we are in looking at it.

Leonardo's Mona Lisa is probably the most famous example. Though that was painted 40 years after Nicholas' death. Nicholas' image is, of course, not that of a woman. He calls it 'the icon of God'. Whether it was a painting of God or of Christ is uncertain. I have found an icon of Christ the ascended Lord that has similar properties. The eyes seem to track you wherever you are.

looking on all around it.'[3] We are familiar with the painted face whose eyes seem to follow us and rest upon us wherever we are in looking at it.

Leonardo's Mona Lisa is probably the most famous example. Though that was painted 40 years after Nicholas' death. Nicholas' image is, of course, not that of a woman. He calls it 'the icon of God'. Whether it was a painting of God or of Christ is uncertain. I have found an icon of Christ the ascended Lord that has similar properties. The eyes seem to track you wherever you are.

Look at this picture. It is a painting by the 19th century German artist Caspar David Friedrich (1774 - 1840) and is entitled 'Monk by the Sea'. Nicholas in 1453 sent a painting of the face of God into the monastery where the monks lived. Friedrich has brought the monk out of the cloister and set him deep in the midst of the natural world. The contrast could hardly be greater. The monastery is a human structure, small scale, secure, close in, manageable. This is nature, vast, untamed, other. The sky towers above the tiny human figure. The sea is dark, shifting, unfathomable. The sand deserted and massive beneath his feet.

Look at this picture. It is a painting by the 19th century German artist Caspar David Friedrich (1774 - 1840) and is entitled 'Monk by the Sea'. Nicholas in 1453 sent a painting of the face of God into the monastery where the monks lived. Friedrich has brought the monk out of the cloister and set him deep in the midst of the natural world. The contrast could hardly be greater. The monastery is a human structure, small scale, secure, close in, manageable. This is nature, vast, untamed, other. The sky towers above the tiny human figure. The sea is dark, shifting, unfathomable. The sand deserted and massive beneath his feet.

nature. And our way of living has damaged the Earth to the point where it begins to threaten the stability and even viability of the great natural systems of water, air, climate, soil, plants, and animals upon which we depend. Perhaps this would be the image he would offer us. Nicknamed 'the eye of God', this is the Helix Nebula, some 700 light years away from Earth in the constellation of Aquarius, as seen by the Spitzer Space Telescope. In the 21st century we need to meet the eye of God gazing upon us and upon all things here in the realm of God's creation itself. For it is here where the forces of destiny are presently gathering.

nature. And our way of living has damaged the Earth to the point where it begins to threaten the stability and even viability of the great natural systems of water, air, climate, soil, plants, and animals upon which we depend. Perhaps this would be the image he would offer us. Nicknamed 'the eye of God', this is the Helix Nebula, some 700 light years away from Earth in the constellation of Aquarius, as seen by the Spitzer Space Telescope. In the 21st century we need to meet the eye of God gazing upon us and upon all things here in the realm of God's creation itself. For it is here where the forces of destiny are presently gathering.