|

|

|

A paper given at a seminar held by the Institute for Spiritual Studies on the 2nd of May, 2013

Delivered by The Rev'd Dr Ross Fishburn, Academic Dean at Yarra Theological Union, a College of MCD University of Divinity

Michael Ramsey on Easter, Transformation and the Church

My title is inspired by some words from his second scholarly work The Resurrection of Christ, published in 1945 when he was Professor of Theology at Durham University. It comes towards the end as he is wrestling with the paradoxes of the church which is both a glorious mystery and at times a glorious mess. He says:

The New Testament suggests the way is to accept the paradox, not with complaisance nor with a sense of grievance but with the light of the Cross and the Resurrection upon it. The man who knows, from the Cross, his own need is not ashamed to put himself beside other members of the Church whose need is like his own; and to discover amid the contradictions of the Church's members the risen life of Christ which is the divine answer to his need as to theirs.[1]

It is now 25 years since his death, almost exactly; he died on April 23rd, and he was buried on May 3rd. The anniversary is tomorrow. So in this Easter season, I want to think about how central the Easter mystery was for Michael Ramsey in his theology, his spirituality and his life, and why it was so. I want to look at both Ramsey's life and his writings.

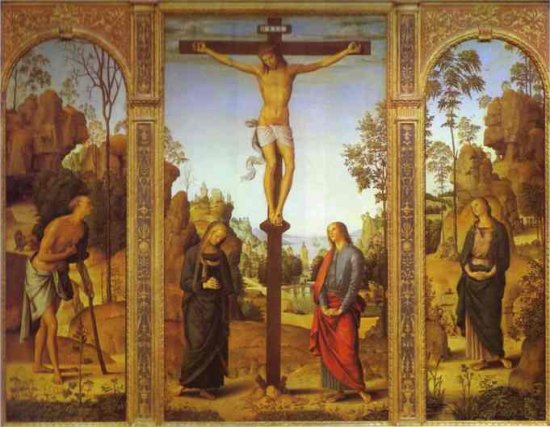

Let me start with a picture.

When he was a student at Cambridge, he brought a print, as young university students do, to decorate their rooms. This picture was by the Italian renaissance master Pietro Perugino (1448-1523), and it's called "Crucifixion with the Virgin, St John, St Jerome and St Mary Magdalene". More commonly it is known as the Galitzin Triptych after the Russian prince who owned it in the Nineteenth Century before donating it to the Hermitage Museum in Moscow. The original is now in Washington.

The picture came to play a significant part in his life, standing in a central place in the living space of house after house. Owen Chadwick, his biographer and friend notes: "It hung on 19 different walls, but never changed its place"[2] That gives me an excuse to give you an outline of his adult life via the rooms in which the picture hung:

- Student rooms first at Magdalene College Cambridge [1923], and then [1927] Cuddesdon Theological College near Oxford

- Curate's digs in Liverpool [1928]

- the Sub- Warden's residence at Lincoln Theological College [1930]

- Curate's digs again at Boston Stump [1937]

- digs again in Cambridge while Vicar at St Benets, [1939]

- thence to Durham [1940] as Canon & Professor, (where he married Joan, the former secretary and driver to the Suffragan Bishop).

- back to Cambridge as Regius Professor of Divinity, [1950]

back to Durham to be Bishop (well Auckland Castle at Bishop Auckland actually) [1952]

- then York as Archbishop,[1956]

- and Lambeth Palace & Canterbury as Archbishop, [1961-74]

- and then retirement in Oxford[1974], Durham [1977] and York [1986], and finally in a nursing home in Oxford [1987].

He bought the picture because he liked it, rather than specifically because it was a crucifixion; but later it came to symbolise what was central to Ramsey's Christianity: God's love shown on the cross as the beating heart of the transforming mystery of redemption.

Perugino's picture of the crucifixion of Jesus is for me a great picture, because it wonderfully shows a large part of what Christianity means. Christ is seen suffering, suffering terribly; and yet in it there is triumph because love is transforming it all. We see the victory of self-giving love. Nothing is, I believe, more characteristic of Christianity than the power, drawn from Jesus Christ, of bringing into the midst of suffering this outgoing love, with its note of victory, serenity, even joy. It is one of the most marvellous things in human life, that just when we are downcast by the problem of evil, the challenge of goodness hits us in the eye and overwhelms us.[3]

Why did Ramsey come to this particular vision of the theological centre of things, and to this way of speaking of it, I wonder? Different theologians and spiritual writers have their real theological and spiritual centre in all sorts of places, and it often comes from some key event in their life, from a conflict, or a formative context that makes that person who he or she is.

Michael Ramsey was a person who had known suffering and despair in his own life and the deep places of the soul. Ramsey's mother died in a tragic car accident when he was a young ordinand at Cuddesdon. His father was driving the car. This tragic loss at a time when he was vulnerable left a deep mark on him, and caused him to suffer depression and to seek treatment from a psychiatrist for several months, visiting 3 times a week. Out of this deeply painful experience, Ramsey brought a faith which came to know God's grace and action as the only thing which reaches our darkness and difficulties, saves and redeems us.

I think that is something of the life context out of which this theology of the cross is carved. As you would expect, it took a while to emerge and be refined. We certainly see it by the time of his first book — The Gospel and the Catholic Church which appeared in 1936. In it he writes about the church and about ministry. He grounds this exploration in a theology of the Easter mystery, in which the cross and the resurrection become the theological ground for the church. His theme is best expressed in the description of the church as "the society in which men die and rise" and in the idea that the church and its ordered ministry are an expression or manifestation of the gospel — an "utterance of the gospel" is the phrase he uses numerous times.

But perhaps the clearest expression his theology of the Easter mystery has is in his second book — The Resurrection of Christ, published in 1945, and subtitled An Essay in Biblical Theology. Here is a key section which shows Ramsey's theme:

The Crucifixion is not a defeat needing the Resurrection to reverse it, but a victory which the Resurrection quickly follows and seals. The "glory" seen in the cross is the eternal glory of the Father and the Son; for that eternal glory is the glory of self giving love, and Calvary is its supreme revelation.

So it is that the centre of Apostolic Christianity is Crucifixion-Resurrection; not the Crucifixion alone nor even the Crucifixion as a prelude and the Resurrection as a finale, but the blending of the two in a way that is as real to the Gospel as it is defiant to the world. ... For Life–through–Death is the principle of Jesus whole life; it is the inward essence of the life of the Christians; and it is the unveiling of the glory of the eternal God.[4]

Life through Death, living a life of self-giving love, this is the purpose of human existence for Ramsey, the end to which we are called and for which we are made. I have called his theology, and especially his ecclesiology Paschal to make the point that the Easter mystery of the dying and rising of Jesus is at the heart of the church, of Christian life, and indeed at the very heart of the divine life in all eternity.

Cross and Resurrection go together, and together they are the seal of the whole life and ministry of Jesus.

Ramsey's Theology of the Paschal Mystery.

There's a difficulty of terminology here. I can't just talk about Easter, because Ramsey's understanding of Easter is complex as we have seen. For him, the Easter event (if you like) is the complex event that we celebrate in the Great Three Days, the Triduum Sacrum. That's what he was saying in the quote I just read, as he talked about Crucifixion Resurrection as the centre of apostolic Christianity.

I could talk about the Easter event if we understood it in this rich sense, but I will also be wanting to talk about how we become part of that event, so I want to talk about the Easter mystery to show that it's more than just what happened back then. So because I want to talk about the rich meaning of Easter, as complex event, and because I want it to be a big enough phenomenon that it catches us up in it, I'm going to use the phrase paschal mystery. [The word paschal of course is used of Easter to remind us of the echoes and carryovers from the Jewish Passover. So we have the Paschal Candle which we bless at the Great Paschal Vigil.]

So I want to talk about Ramsey's theology of the paschal mystery as a great complex event that is both crucifixion and resurrection, and which is so big a mystery that we become part of it. There are four key themes in Ramsey's paschal theology.

1 The paschal mystery is the purpose of Jesus' life and work.

God in Christ comes to "do" Easter, if you like. That's the heart and centre of Jesus work.

That might be a surprising theological insight, or it might seem quite commonplace to you. You might think God's chief purpose in sending Jesus was for him to die on the cross for our sins. But you might think that the chief purpose in Jesus life was his teaching or his miracles, that he came to show us God and how to live God's way, that he came to teach us.

Well Ramsey's theology says yes to both, and doesn't want to say either is wrong but rather to hold them together. What Jesus shows us of God in the miracles, and teaches us about God in the parables and in other places, is what Jesus lives out in the great events of his dying and rising. Let's hear this in Ramsey's own words:

The Gospel of God appears in Galilee: but in the end it is clear that Calvary and the Resurrection are its centre. For Jesus Christ came not only to preach a Gospel but to be a Gospel, and he is the Gospel of God in all that he did for the deliverance of mankind.[5]

The good news that Jesus proclaimed was the coming Reign of God. The reign had come. Both the teaching and the mighty works of the Messiah bore witness to it. The teaching unfolded the righteousness of the Kingdom, and summoned men and women to receive it. The mighty works asserted the claims of the Kingdom over the whole range of human life. The healing of the sick; the exorcism of devils; the restoration of the maimed, the deaf, the dumb, and the blind; the feeding of the hungry; the forgiveness of sinners; all these had their place in the works of the Kingdom. But though the Kingdom was indeed here in the midst of men, neither the teaching nor the mighty works could enable its coming in its fulness. For the classic enemies — sin and death — could be dealt with only by a mightier blow, a blow which the death of the Messiah Himself alone could strike. And the righteousness of the Kingdom could not be perfected by a teaching and an example for men to follow; it involved a personal union of men with Christ Himself, a sharing in his own death and risen life. Thus He had a baptism to be baptized with, and He was straightened until it was accomplished. But when it was accomplished there was not only a Gospel in words preached by Jesus, but a Gospel in deeds embodied in Jesus Himself, living, dying, conquering death. ... Thus it was that the Gospel preached by Jesus became merged into the Gospel that is Jesus.[6]

The Gospel which Jesus proclaimed, is the Gospel which Jesus lived, and died, and which could not be held by death, could not be kept captive in the grave; this is gospel or good news of self-giving love, of Life through Death. In his first book he called it dying to self-sufficing. And as we have seen in that first quotation from his resurrection book, it is unveils the eternal glory of God.

2 The Paschal mystery shows us the heart of God

(the full measure of the divine glory)

So the Paschal Mystery, the complex event of Easter, unveils God's eternal glory. It shows us what is at the heart of God's life and God's nature and being, which is self-giving love. We might say that the good news, the gospel is not just of a sacrifice that Jesus makes once for all on Calvary, but that the gospel is the sacrifice (the perpetual offering) that God is from eternity and which is enacted or externalized in the paschal event.

Ramsey keeps saying something about this throughout his life: "the glory of God in all eternity is that ceaseless self-giving love of which Calvary is the measure".

He wrote it thus in his little book God, Christ and the World in 1969, but the concept and the elements of it keep getting reiterated from 1945 onward, and it utterly consistent with what he writes in his first book in 1936 as well.

This book was a considered theological response to the avant garde theology of the 1960's — not just J.A.T. Robinson's Honest to God, but all the death of God movement. This is Ramsey's response:

The self-giving love of Calvary discloses not the abolition of deity but the essence of deity in its eternity and perfection. God is Christlike, and in him is no un-Christlikeness at all, and the glory of God in all eternity is that ceaseless self-giving love of which Calvary is the measure. God's impassibility means that God is not thwarted or frustrated or ever to be an object of pity, for when he suffers with his suffering creation it is a suffering of a love which through suffering can conquer and reign. Love and omnipotence are one.[7]

Calvary is the key to omnipotence which works only and always through sacrificial love. ... Divine omnipotence and divine love (in terms of history a suffering love) are of one. And the assertion of this is meaningful when we are ourselves made one with the crucified and in his spirit can say 'All shall be well, and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well.'[8]

It's very Johannine really. Think of John 1:18 "No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son who is close to the Father's heart who has made him known". What Jesus makes known is who God is from the beginning, and that is love which pours itself out to the end and beyond. We see God's glory in Jesus, from his beginning and thereby from God's beginning, and we see it as Jesus is lifted up on the cross. This is the glory of self-giving love, love poured out that all might be drawn to God. The glory which the paschal mystery shows in full is the full measure of the eternal glory of God, "the ceaseless self-giving love of which Calvary is the measure".

3 The Paschal mystery is the beginning or the origin of the Church

In expounding the paschal mystery as showing us God's way of self-giving love there have been glimpses already of the next aspect of Ramsey's paschal theology. It is not just about eternity and God, and not just about back then. It about us, and about now and the future for us. That comes in two aspects: the church and transformation. First let's look at paschal theology and the church.

This is really one of the key points which Ramsey wanted to make in his first book: The Gospel and the Catholic Church, which he conceives as a study of the Church, its doctrine, its unity and its structure, in terms of the Gospel of Christ crucified and risen. Thus the preface begins:

"The underlying conviction of this book is that the meaning of the Christian Church becomes most clear when it is studied in terms of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ." [9] He goes on to state that, "The right interpretation of the church's task in this present as in every age, will begin with the Biblical study of the Death and Resurrection of the Messiah, wherein the meaning of the church is contained."[10]

Ramsey presents the paschal mystery as both the origin of the church, and more deeply, its determining factor. The Easter mystery and the mystery of the church are inextricably linked, because the meaning of the church is contained in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This understanding of connection between the church and paschal mystery relies on a strong understanding of corporate personality; for him the church is contained in this one complex event.

The death and the Church — the one has sprung from the other. Yet the connection is closer still. For it seems not only that Christ creates the Church by dying and rising again, but that within him and especially within His Death and resurrection the Church is actually present. We must search for the fact of the Church not beyond Calvary and Easter but within them. [11]

Here then is a complete setting forth of the meaning of the Church: the eternal love of the Father and Son is uttered in Christ's self negation unto death, to the end that men may make it their own and be made one. .... [The] death to self qua self, first in Christ, and thence in the disciples is the ground and essence of the Church.[12]

God raised him, and in death and resurrection the fact of the Church is present. For as He is baptised into men's death, so men shall be baptised into His; and as He looses His life to find it in the Father, so men may by a veritable death find a life whose centre is in Christ and in the brethren. One died for all therefore all died. To say this is to describe the Church of God.[13]

Just as Jesus is "baptised into men's death" (entering fully into the human experience of death), so too the death of Jesus opens for all humanity the possibility of participation in the divine life, by our baptism into his death.

But this event, born in eternity and uttering the voice of God from another world, pierces deeply into the order of time, so that the death and resurrection of Christ were known, not only as something "without" but also as something "within" the disciples who believed. That is the meaning of the Church.[14]

Just as the first disciples come to be shaped in the same pattern as Christ's death, themselves dying to "separate and sufficient selfhoods",[15] and find themselves alive in each other and in the Spirit, so too all of us in the church respond to God in the same pattern. The response of faith in the believer is first an owning of one's own nothingness, and thus is a dying to self. In so responding, we come to be sharers in the death and resurrection:

Nor is the Christian's death to self only a response to the death of Christ as a past event; it is a present sharing in His dying and rising again. In Baptism the death and resurrection of Jesus become a present reality within the converts. [he quotes Romans 6:3-11] By the power of the Spirit who brings the self-giving of God into the convert's life the self-centred nexus of appetites and impulses is broken, and the life is brought into a new centre and environment, Christ and His Body.[16]

Here then we see Ramsey's theology of participation in the paschal mystery. In receiving the benefits of Christ's death as a faith response, and in the fact of our baptism, we come to have fellowship with the paschal events themselves, and we participate in the dying and rising of Christ.

Thus Christians have looked back to the death and resurrection of Jesus on whom they first believed , they have received the Spirit of him who died and rose again, they have known the dying and rising as a fact within themselves.[17]

The strong link between the church and the death and resurrection of Jesus has a further consequence for Ramsey's theology of the church. Participation in Christ's death comes to have a quality which continues to shape the individual's life and corporate character of the church. The new environment into which a Christian is drawn is one in which self has been crucified and we are brought into a new humanity of which Christ is the head, and our lives are given a new centre. Membership of the Church involves dying to "self-sufficing", and brings us into what Ramsey memorably calls "the society in which men die and rise."[18] Thus he speaks of the church as a "scene of continual dying",[19] and "the fellowship whose very meaning is death to self."[20] This different sort of life is enabled by the gift of the Spirit, who is seen as inextricably linked with the cross. "Not only did the crucifixion make possible the giving of the Spirit, but the life bestowed by the Spirit is a life of which crucifixion is a quality, a life lived through dying."[21]

The church is the society in which we die and rise; it is an extension, a further working out of the paschal mystery. And because the paschal mystery is worked out in the church, it gives the church a paschal character. [Rowan Williams makes a similar point when he says: "where there is salvation its name is Jesus; its grammar is the cross and resurrection."] It shows paschal mystery, it shows Easter in all it does.

4 Transformation and Transfiguration flow from the Paschal mystery as we are caught up in it.

So, as members of the Church we die and we rise with Christ, and in so doing we are transformed, we have a new centre of our being, a new way of living, the way of death through life, the way which has died to self-sufficing.

Here's another passage from God, Christ and the World which shows the link to our living.

The Christlikeness of God means that his passion and resurrection are the key to the very meaning of God's own deity. Is there within and beyond the universe any coherence or meaning or pattern or sovereignty? The New Testament doctrine is that in the death and resurrection of Jesus, in the fact of living through dying, of finding life through losing it, of saving of self through the giving of self, there is this sovereignty. And to believe with more than a bare intellectual consent is to believe it existentially, and to believe it existentially is to follow the way of finding life through losing it. Those who make their own the living through dying of Jesus find purpose, sovereignty, deity, in and beyond the world. [22]

When they came to dedicate a window in honour of Ramsey in his beloved cathedral in Durham a few years ago, they chose to make it a window depicting the transfiguration, and they placed a little portly balding figure in it to show him. His former chaplain John Andrew preached for the occasion. And recalled what Ramsey himself called the transfiguration method.

Ramsey taught "You place the events and circumstances which daunt you, and frighten you, and damage you, in the setting of the Eternal — just as Christ himself upon the Mount with his Passion and death before him was observed to be transfused with light, the Shekinah. "We are," his chaplain recalled his saying, "to avail ourselves of the liberation, from fear, despair, cowardice, and compromise, if we can see the things that frighten us within the transfiguring frame."[23]

PART 2

Bishop Stephen Cottrell of Ely has recently recalled this story:

Ramsey had a particular human and institutional pain to bear in the person of Lord Fisher, his predecessor as Archbishop of Canterbury who had sought to block Ramsey's candidacy by trying to bully Harold Macmillan, the Prime Minister. Fisher had been Ramsey's headmaster at Repton and thought that this gave him the right to send Ramsey several letters each week detailing Ramsey's faults. Lady Fisher never posted more than three a week. Ramsey became quite depressed and stopped singing and talking to himself in his wonted Pooh Bear manner. Mrs Ramsey and the Chaplain were quite worried, even more so when one morning he went off in the car alone. When he returned, he was his old singing self. He rejoiced to tell them, "I have been to Madame Tussauds', I have been to Madame Tussauds', and they boiled down Geoffrey Fisher and turned him into me!" [24]

How does this method of transfiguration help us discover the risen Christ in the midst of the mess?

I have a sheet in a file passed on to me by Bishop Grant while I was doing my doctoral research. It's entitled Five helps for the New Year. It says:

- 1. Thank God. Often and always. Thank him carefully and wonderingly for your continuing privileges and for every experience of his goodness. Thankfulness is a soil in which pride does not easily grow.

- 2. Take care about confession of your sins. As time passes the habit of being critical about people and things grows more than each of us realize. ...[He then gently commends the practice of sacramental confession].

- 3. Be ready to accept humiliations. They can hurt terribly but they can help to keep you humble. [Whether trivial or big, accept them he says.] All these can be so many chances to be a little nearer to our Lord. There is nothing to fear, if you are near to the Lord and in his hands.

- 4. Do not worry about status. There is only one status that Our Lord bids us be concerned with, and that is our proximity to Him. "If a man serve me, let him follow me, and where I am there also shall my servant be". (John 12:26) That is our status; to be near our Lord wherever He may ask us to go with him.

- 5. Use your sense of humour. Laugh at things, laugh at the absurdities of life, laugh at yourself.

Through the year people will thank God for you. And let the reason for their thankfulness be not just that you were a person whom they liked or loved but because you made God real to them.

How did he do it?

The church may need to have its heart broken (1961).

Ramsey was a man who knew the cross, and he knew that the cross wasn't something that you should run away from, but actually was where God was most at work. He showed this in the time between the announcement of his appointment and his move to Lambeth.

Before his enthronement, Ramsey was asked whether he was in good heart at being about to become Archbishop of Canterbury; his response was that he was,

But the phrase "in good heart" sometimes gives me pause, because after all we are here as a church to represent Christ crucified and the compassion of Christ crucified before the world. Because that is so, it may be the will of God that our Church should have its heart broken, and if that were to happen it wouldn't mean that we were heading for the world's misery but quite likely pointing the way to the deepest joy.[25]

One of the focusses for the particular cross Ramsey had in Geoffrey Fisher was his leadership of the Church of England in its rapprochement with the Methodist Church. It was, I think, a time when Ramsey had his heart broken, and I thought I'd tell you some of that story tonight.

When Ramsey succeeded Fisher as Archbishop, one of the projects he inherited was the Anglican Methodist Unity Scheme. It had started with a speech from Fisher in 1946 when he suggested that rather than aim at full unity, churches might grow alike, and as part of this, that Free Churches might "take episcopacy" into their systems. Only the Methodists were prepared to think about this. By 1961 it had all proceeded as far as talks about talks, that is official discussions hadn't begun and no concrete proposal had been advanced but ground clearing talks had progressed well. The interim report had identified the key problem of what would happen with the Methodist ministers under any sort of united church, since they hadn't been ordained by bishops, they couldn't be recognized as in any way equal in the Church of England.

The Unity scheme dogged Ramsey's period as Archbishop. The stages of the process ended up being an initial proposal in 1963, which was extensively discussed around the two churches, then an interim report (1967), a formal proposal in 1968, and extensive consultation by the churches, discussions in the convocations in 1968 and a voting process in various places as well as convocation in 1969. This process failed to settle the matter. It was the old story of a simple majority when a two thirds majority was required.

Now at that point the Church of England was about the introduce Synodical government (yes that's right, just a century after we did here in Melbourne!), so it was referred to the new Synod when that came into existence. That happened in 1972. It failed.

So what was the problem?

Well, as I said, there was a difficulty about the standing and recognition of Methodist minister in a new united church. It's a perennial problem in ecumenical reconciliation. Solutions vary from having bishops re-ordain all of them, to deciding to tolerate a period where not all the clergy would be episcopally ordained. What this scheme decided to do was to have a service of reconciliation in which the leaders of both churches would submit to the laying on of hands, to "make" the ministry of this new reconciled church. The Methodist leaders would go first, and receive the laying on of hands from Anglican Bishops, and then the Anglican Bishops would receive the laying on of hands by the Methodists leaders (who would now be bishops). But the problem was, would this whole thing be an ordination?

Ramsey's answer was almost that this was the wrong question and it didn't matter.

It is my own belief that if the proposals set out in the report were carried out successfully the essential catholicity of our Church of England would be in no way compromised. That is my own belief and conviction. Let me come particularly to the service of unification and particularly to the points about it, questions about it (sic)... It seems to me quite clear that it is the intention of the act that those who receive the laying on of hands shall after that act be undoubtedly priests in the Church of God. That is the intention which is clear in the prayer; that seems to me to be without any doubt whatever. What is not defined and what is doubtful is the present status of people's ministries, and that is a thing that any of us might shrink from defining. People's present condition isn't defined, the goal of the act which makes all alike priests in the Church of God, undoubtedly priests and possessing the same authority in the Church of God is absolutely clear.[26]

We know that our own orders are completely regular from a catholic standpoint. We do not know the exact relative status and value in God's eye of the existing Methodist ministry, i.e. it is impossible to equate it with what we call "the apostolic ministry" used and blessed by God through the continuous life of a Christian community. I should therefore be entirely ready as a Bishop to take part in the laying on of hands on Methodist ministers of this generation asking God to give them what he knows they need in grace and authority in order that their ministry may be in status, office and authority identical with our own. It is in that sense "agnostic" but it is not a novel kind of agnosticism as I am frankly agnostic already about the status of a Methodist minister. For my part I am ready to receive the laying on of hands from Methodist ministers asking God to give me not indeed apostolic authority (because I believe I already possess that) but an added significance to my ministry which will come to it through the divided Churches becoming one.[27]

In a letter to a priest who confessed he would have been happy with the Service of Reconciliation had it been clearly an ordination, Ramsey replied:

We cannot exactly call it an ordination, mainly because it is doing what no ordination does, namely uniting the whole ministry of a Church or Christian community which we can neither affirm to be catholic priesthood nor affirm to be nothing at all. I cannot say "this is an ordination" but I can say without hesitation "this will effect by God's action all that an episcopal ordination can effect."[28]

But that sort of agnostic response didn't satisfy either end of the spectrum: some evangelicals like JA Packer and Colin Buchanan believed that it was an ordination and it shouldn't be because it insulted the Methodists; some Anglo-Catholics like Graham Leonard believed it wasn't an ordination because it didn't say it was, and it needed to be! [Interestingly, Eric Kemp who later came to side with Leonard over the ordination of women issue was one of the key organisers for the scheme.]

In 1972, the General Synod had voted in favour of the Church of England being in full communion with the Church of North India, a united church which had used almost exactly this method of reconciling the ministries of the churches. But what was Ok in North India was not good enough at home. Go figure!

Ramsey maintained his positive view of throughout, even though it was looking grim. His last words in the synod debate was almost a cry against the inevitable: he quoted the musical Godspell — Long live God! Long live God!

Publicly Ramsey maintained a brave face. Privately it was a different story. If you read the correspondence in his official papers, you can see a spectrum of pain, revelaed only in full to those closest to him.

Two examples must satisfy us:

Here is his reply to a telegram of sympathy from our own Frank Woods (Primate of the Australian Church at that time):

Thank you for your telegram. I was very glad to have it.

I am of course grieved at the Anglican Methodist set back, though by no means surprised. What grieved me most was not the failure so much as the remarkable inadequacy of the opposition case to which we listened. I have a feeling that advance is now going to be on a different kind of plane and that, with great risks of anarchy, local developments are going to prepare the way for the next phase of solutions.

With my love and gratitude, yours ever.

(dictated but not signed owing to absence).[29]

Yet to an old friend, Geoffrey Curtis of Mirfield, he said,

What does one do? It is very painful. But I think the call is to stay and not to despair. ... So we stay, and serve the Lord painfully and joyfully. What has vanished is the idea that being an Anglican is something to be commended to others as a specially excellent way.[30]

So we stay, and serve the Lord painfully and joyfully.

He had seen it coming, even if he didn't show it in public. Prior to the Synod vote he had written to Donald Coggan the Archbishop of York:

If we fail on 3rd May our position as a Church will be humiliating, and other Churches will have confidence if we begin to learn humility and discover that in this matter we are at the listening and not the initiating end.[31]

But that's the thing with Ramsey, and with paschal theology, you may have your heart broken, and you may need to be humiliated, and work from that place, because the church isn't perfect, but is rather the place, the society in which we die and rise, and as a result we aren't in control.

In fact Ramsey had known this all along in his theology. In his first book he wrote of the church needing to learn and re-learn its theology in humiliation, as at the church door in Wittenberg (with Luther).[32]

He concludes the second last chapter of that book with these words, which I find hopeful and encouraging when the church is at its worst.

For while the Anglican Church is vindicated by its place in history, with a strikingly balanced witness to gospel and Church and sound learning, its greater vindication lies in its pointing through its own history to something of which it is a fragment. Its credentials are its incompleteness, with the tension and travail in its soul. It is clumsy and untidy, it baffles neatness and logic. For it is sent not to commend itself as "the best type of Christianity" but by its very brokenness to point to the universal Church wherein all have died. Hence its story can never differ from the story of the Corinth to which the Apostle wrote. Like Corinth, it has those of Paul, of Peter, of Apollos; like Corinth, it has nothing it has not received; like Corinth it learns of unity through its nothingness before the Cross of Christ; and like Corinth, its sees in the Apostolate its dependence upon the one people of God, and the death by which every member and every Church bears witness to the Body which is one.[33]

The church is the society in which we die and rise, the epiphany of God's action in the paschal events (as Rowan Williams has summed up Ramsey's ecclesiology), and when it feels like we are in the midst of the three days in the tomb, we hang on to the certainty that we will rise with Christ because we have risen with him in our baptism.

Perhaps we might conclude with the Bidding from the beginning of the memorial service at Westminster Abbey in June 1988.

- We come to praise God for his servant Michael Ramsey: to celebrate his leadership, his scholarship, his care for Christian unity and his pastoral heart; but chiefly his prayerfulness and his humanity.

From him we learned more of the sovereignty and the Christlikeness of God, and "the glory of God in all eternity (which) is that ceaseless self-giving love of which Calvary is the measure".

We recall with delight his presence, his voice, his laughter, the times of reverie: that mixture of shyness and courageous resolution born of deep conviction. Sometimes so awkward a conversationalist, always so eloquent a communicator of the things of God, he was a man full of affection for the human race and all who knew him came to love him.

Notes

- A.M.Ramsey, Resurrection of Christ, London: G.Bles, 1956 edition, p98.

- O.Chadwick, Michael Ramsey: a Life. Oxford: OUP, 1990. p369

- D.Dales, J.Habgood, G.Rowell & R.Williams, Glory Descending: Michael Ramsey His Life and His Writings. Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2005. p50.

- A.M.Ramsey, The Resurrection of Christ. p19.

- Ramsey, The Resurrection of Christ. p8.

- ibid., p9-10.

- A.M.Ramsey, God, Christ and the World: a Study in Contemporary Theology. London:SCM, 1969. p41.

- ibid., p42.

- Ramsey, The Gospel and the Catholic Church. London: Longmans 2nd edition, 1956. p vi.

- ibid., p vii.

- ibid., p 19.

- ibid., p 25,26.

- ibid., p 27.

- ibid., p 28.

- ibid.

- ibid., p 32,33.

- ibid., p 33.

- ibid., p 44.

- ibid., p 41.

- ibid., p 66.

- ibid., p 30.

- Ramsey, God, Christ and the World. pp99-100.

- John Andrew Sermon at Ely

- Bishop Cottrell of Ely

- A.M.Ramsey, The Christian Priest Today. pp99-100.

- Canterbury Diocesan Conference, Nov 23, 1963. (Verbatim record of Ramsey's speech, p36.) Pamphlet bound with 1963 Report in Lambeth Palace Library.

- Ramsey to Prof. M.Deansley, 15/7/68, Ramsey Papers, Vol 143, f.12.

- Ramsey to Cyprian Dymoke-Marr, 17/1/69, Ramsey Papers, Vol 165, f.89.

- Reply to telegram from Frank Woods, Archbishop of Melbourne, 26/5/72. Ramsey Papers 1972.

- Chadwich, Ramsey, p346.

- Letter to Abp. of York, 17/3/72, Ramsey Papers, 1972. At the time of accessing this material, none of the 1972 papers had been foliated or bound.

- Ramsey, The Gospel and the Catholic Church, p180.

- Ramsey, The Gospel and the Catholic Church, p220.

Top |

Reports |

ISS Home

This site is hosted by St Peter's Eastern Hill,

Melbourne, Australia.

Content is authorized by the

Institute for Spiritual Studies

Maintained by the editor

(editor@stpeters.org.au)

|